| Landboreformer

| | På begge sider af Sundet fandt der i sidste trediedel af 1700-tallet nødvendige og omfattende landbrugsreformer sted.

I Nordsjælland var det kronens gods, der i første omgang blev et eksperimentarium for en ny opdeling af jorden.

I Skåne var det Storgodsejeren Rutger McLean på Svanholms gods, som påbegyndte reformerne. |

Landboreformer - Sjælland

| | Nordsjælland var et centralt område i den første store reformbølge. Bl.a. fordi at man her kun skulle forholde sig til én godsejer, nemlig kronen.

Reformen betød bl.a. en ændring af kulturlandskabet, hvor de store skovarealer blev indskrænket.

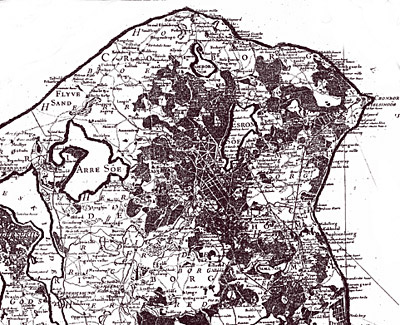

På kortet over Nordsjælland fra 1768 ser man, omend lidt overdrevet, skovenes dominans før reformerne slog igennem.

|

Landbrugsreformer

Fra midten af 1700-tallet kommer der i Danmark en offentlig debat om land- og skovbrugsforholdene. Debatten er karakteristisk for oplysningstiden og den oplyste enevælde, hvor kongemagten på visse områder går i dialog med oplyste kredse i samfundet for at skabe nytænkning og udvikling. Et gennemgående synspunkt i debatten er at græsning og gærdeshugst er væsentlige årsager til skovenes slette forfatning og at man bør sigte på klarere brugsbestemmelser og adskillelse af skov og landbrug.

Jord og arbejdskraft

Den dyrkede jord der sorterede direkte under kronen i Nordsjælland var organiseret under fem ladegårde: Frederiksborg, Esrom Kloster, Kronborg, Kollerødgården og Ebbekjøbgården (senere Tulstrup og Knorrenborg Vang). Alle gårdene var bortforpagtet, bl.a. til amtslige embedsmænd, frem til 1717.

Kronens havde behov for leverancer af vildt, madvarer, brænde m.m., og havde derfor stor interesse i den arbejdskraft som bønder og husmænd leverede igennem hoveriarbejdet. For bøndernes vedkommende var der principielt ingen begrænsning i hoveriet, som udover omfattende arbejde med høslet for stutteriet og skovarbejde også omfattende kørsel for hoffet, hvor man undertiden skulle mønstre 100-200 vogne. Hertil kom f.eks. også transport af fødevarer og lån af sengeklæder. Husmændene var i reglen både håndværkere og landarbejdere, men havde dog den fordel at de kun skulle levere en dags hoveriarbejde om ugen.

Ryttergodset.

Årene 1713-14, midt under Den store nordiske Krig, var udprægede kriseår for jordbruget, bønderne forarmedes udover evne og amtmand von Raben tager initiativ til en gennemgribende reform, hvor man skulle opgive korndyrkningen og overgå helt til høslet på markerne, udleje høslættet i skovene og sigte på at ophæve hoveriet.

Så vidt kommer det dog ikke, men i 1717 vedtages en gennemgribende reform om udlægning af ryttergods, hvorved i Nordsjælland 40 tdr. hartkorn jord udlægges til underhold af 120 ryttere og heste. Landsbyer nedlægges, ladegården i Kollerød udlægges til ryttergårde for en officer og 30-40 ryttere og i Esrum opføres rytterbarakker. Bønderne skulle være med til at underholde rytterne, men den fortsatte forarmelse medfører at man i 1723 må eftergive bøndernes restancer i rytterpenge.

Stutteriets dominans

Rytterreformen er som udgangspunkt en militær reform, som også bringer en vis forandring i de dyrkningsstrukturelle problemer. Et problem havde man dog ikke imødeset, nemlig at der som følge af inddragelsen af den dyrkede jord opstår problemer med fødevareforsyningen i de større købstæder, heriblandt Helsingør..

Vigtigst var dog nok at man nu satsede ensidigt på produktion af hø til det kongelige stutteri, som sammen med ryttergodset kommer til at optage størstedelen af produktionsjorden i Nordsjælland. I 1720 er man således fra de oprindelig 10 nu kommer op på næsten 50 græsningsvange med et samlet areal på 62,5 kvadratkilometer. Antallet af heste var i første halvdel af 1700-tallet op imod 1600 og man havde behov for omkring 8000 læs hø og græs årligt.

Stutterivange 1720 |

Stutterivangene 1765. |

Høsletsarealerne

Behovet for foderhø i stutteriets storhedstid var altså ganske enormt og stort set alt blev taget i brug. Bedst egnede til både høslet og eftergræsning var dog de opdyrkede områder og skovengene, specielt i den vestlige del af det nuværende Gribskov. Strø Vang omkring det nuværende Strøgårdsvang var deciderede høsletseng, mens andre arealer også anvendtes til græsning i større eller mindre omfang.

Det enorme behov for arbejdskraft blev på længere en hæmsko for ophævelse af hoveriet i Nordsjælland, men det forhindrer dog ikke at Nordsjælland på andre områder kommer tidligt med i reformprocessen.

Græssende heste |

Træbevoksningen |

Græsningsskoven |

Høsletseng |

Strøgårdsvang |

Udskiftning og udflytning

I 1757 nedsættes en kommission ”til landvæsnets fremtarv og nytte”, hvilket i 1758 resulterer i tre udskiftningsforordninger for Sjælland, Møn og Amager. Forordningerne sigter hovedsagelig på at ophæve fællesskabet på overdrevene imellem en landsbys medlemmer, eller flere landsbyer.

Private godsejere eksperimenterede i de efterfølgende år med mere vidtgående reformer og i 1766, efter Christian VII.s tronbestigelse, påbegyndtes reformer med ophævelse af fællesskabet imellem bønderne på krongodset i Københavns amt. Endnu en kommission, i 1768 omdannet til Generallandvæsenskollegiet, kommer i 1769 med en mere vidtgående udskiftningsforordning som tager sigt på at overdrev også inden fire år skal være ”delte og fralukkede” og fra 1776 sættes fokus på udflytningen og der stilles midler til rådighed herfor.

Nordsjælland 1768 |

Nordsjælland 1777 |

Stjerneudskiftning |

Udskiftningsreformer |

Den lille Landbokomission

I 1784 nedsættes en landbokommission for Kronborg og Frederiksborg amter, den såkaldt Lille Landbokommission, og herefter går det stærkt med udskiftningerne i Nordsjælland: i 1789 er jorden udskiftet i 113 landsbyer og året efter er man færdige. Samme år er ikke mindre end 423 gårde og 257 huse udflyttede og dermed er landskabet for alvor ved at skifte karakter. Småskovene og de spredte træer på overdrevene er forsvundet, det dyrkede areal er forøget på bekostning af overdrevene og gårde og huse rejses i det åbne land, således som det fortsat er tilfældet.

Udskiftningen var det vigtigste resultat af Den lille Landbokommissions arbejde og tillige den reform der har størst betydning for ændringen af kulturlandskabet. Andre opgaver var afløsningen af hoveri og tiende med pengevederlag og desuden arbejdedes der for at udbrede kendskabet til bedre sædskifte med nye afgrøder som f.eks. kartofler. Endelig opførtes i de to daværende amter ikke mindre end 35 skoler i årene 1784-90.

Nordsjælland som eksperimentarium

Når Nordsjælland blev valgt som fokus for den lille landbokomission og dermed den første store reformbølge hang det naturligvis sammen med at man her kun skulle forholde sig til en godsejer, nemlig kronen, eller om man vil staten. Desuden var det af to årsager en forholdsvis overskuelig opgave. Krongodset omfattede kun omkring 160 landsbyer med omkring 1300 gårdejere og hertil kom at en stor del allerede var udskiftet ved de første reformbestræbelser tilbage i 1760erne og 70erne.

Det er nok også forklaringen på at ændringerne i landskabets karakter tydeligt kan øjnes allerede på kortet fra Videnskabernes Selskab fra 1777, sammenlignet med et tilsvarende kort fra 1768. Udskiftningskort for de enkelte landsbyer giver et detaljeindblik i processen og ændringerne på lokalt plan. På udskiftningskortet fra Horserød kan man f.eks. tydeligt iagttage det gamle og nye dyrkningsmønster, hvorledes overdrevsjord og tidlige skovareal inddrages i processen og en klar adskillelse imellem agerjord og skov opstår.

Nordsjælland 1777 |

Sandflugt og skovrejsning

Sandflugt og vandreklitter har sammenhæng med skovfældning og overgangen til landbrugsproduktion og allerede i 1200-tallet er der tegn på tiltagende sandflugt. Den middelalderlige krise i 1300-tallet i forbindelse med Den sorte Død, nedgang i befolkningstallet og ødegårde giver landskabet mulighed for at regenerere og på Sjælland springer tidligere landbrugsområder flere steder i skov. Den situation varer frem til engang i 1600-tallet, hvor befolkningsstigning, krig og ødelæggelse igen udsætter naturgrundlaget for øget pres.

I Nordsjælland er tidligere rige landbrugsområder nord for Arresø opgivet og indsejlingen til både Arresø og Søborg sø er blokeret. I starten af 1700-tallet er situationen under hastig forværring i Nordsjælland og f.eks. også på Bornholm og statsmagten tager nu initiativ til at bremse denne udvikling. Som i tilfældet med skov- og landbrugsreformerne tager man først fat i Nordsjælland.

Sandflugten |

Læhegn og beplantninger

I 1702 klagede Tisvilde og Tibirkes beboere deres nød til kongen med henvisning til at sidstnævnte landsby var næsten ødelagt af sandflugten. Bønderne får hjælp til at opsætte gærder og nedslag i skatten, men først i 1724 bliver der taget initiativ til en mere målrettet bekæmpelse med ansættelse af Ulrich Röhl til ”Inspektør ved flyvesandet på Kronborg Amt”. Der plantes ved indforskrevne hovbønder marehalm og hjelm og beklædes med græstørv i en 15-årig periode.

På Videnskabernes Selskabs kort fra 1777 bemærker man, at der i sammenhæng med den generelle reduktion af skovarealet faktisk også er tale om skovrejsning langs Nordkysten, bl.a. de områder der i dag rummer Asserbo og Hornbæk plantager. Disse områder er tilplantet med henblik på at stoppe den tiltagende sandflugt, som efterhånden havde udartet sig til en økologisk katastrofe i hele landet og ligeledes i Skåne.

Beplantningerne følges op med læhegn i form af skovbeplantninger. Den første påbegyndes i 1726 ved Tisvilde. Tisvilde Plantage udvides i 1793 med 27,5 ha skovfyr, samme år anlægges 14 ha ved Hornbæk og i 1799 følges op med en beplantning ved Sonnerup Skov i Odsherred.

Bekæmpelse af sandflugt |

Skåne

| | På Svanholms gods i Skåne blev der påbegyndte reformer indenfor landbruget, som igen banede vej for industrialiseringen.

Dog ikke uden voldsom modstand fra bønderne. |

Det forældede landbrug

En landsby i Skåne udgjordes fra gammel tid af en sammenholdt bebyggelse med opsplittede jordbesiddelser. Det opdyrkede område bestod af dele af vidt forskellig kvalitet. Retfærdighed var blevet tilstræbt ved at give flere mindre markstykker af forskellig kvalitet til hver enkelt bonde. Området blev derfor opsplittet i et stort antal små agre, og situationen blev med tiden uoverskuelig pga. arvedeling.

Omkring 1750 blev man klar over, at en rationalisering af landbruget krævede større og bedre sammenholdte enheder. De stigende priser på landbrugsprodukter, som hængte sammen med den stigende befolkning i Europa i midten af 1700-tallet, krævede forandringer. Samtidigt var landbruget i Skåne blevet forringet af jorderosion, sandflugt, krigens hærgen og vanrøgt. Linné havde, under sin rejse i Skåne, bemærket problemerne med det forældede skånske landbrug.

”Bonden i Skåne holder ligeså ihærdigt fast ved sine forfædres vaner, som vor tids ungdom er hurtig til at forandre dem.”

Forårspløjning |

Reformforsøg

Mens bonden vogtede på sine gamle metoder viste myndigheder og enkelte godsejere interesse for at rationalisere. En plan var, at gennemføre et ejerskifte, så at hver bonde fik større men færre besiddelser, dvs. en udvikling imod større enheder.

For at løse problemet med den svingende jordkvalitet gav man ”karakterer” til de forskellige agre. Gennem at bonitere (kvalitetsbestemme) jorden skulle man bytte god jord mod ringere med større areal. Denne plan blev fremført af inspektoren ved Landmålingen, Jacob Fagott, i hans bog ”Det svenske landbrugs hindring og hjælp” (1746). Ifølge Fagotts idéer ville han beholde byerne men agrene skulle slås sammen til mere sammenhængende enheder. I 1757 udfærdigedes en kundgørelse om udskiftningsreform i Skåne.

Mange bønder var modstandere af denne reform. Man var bange for en uretfærdig fordeling af jorden, ulemper med marker som lå alt for langt fra byen samt problemerne med et større areal med ringere jord, når der var mangel på billig arbejdskraft. Udskigtningen blev derfor ikke helt fuldført, og regeringen trak deres dekret tilbage i en ny kundgørelse i 1783, i hvilken det blev bestemt, at hver bonde måtte have op til otte agre.

Udskiftningsreformen blev med andre ord ikke nogen succes. Brugernes marker var stadigvæk opdelte om end ikke i samme omfang som tidligere.

Macleans planer - en oplyst despot

En mere radikal forbedring af landbruget krævede måske, at bondens gård placeredes der, hvor hans marker lå. Rutger Maclean på Svaneholms gods i det sydlige Skåne havde tanker i den retning. Han var formentlig påvirket af de Udskiftningsreformer, man havde gennemført i Danmark efter 1781, men lignende reformer var også tidligere blevet gennemført i England, som den rejsevante Maclean havde besøgt flere gange.

I 1780´erne gennemførte han en radikal landbrugsrevolution på sit eget gods. Som en mand af oplysningstiden, var han ikke bange for at bruge de metoder, som en oplyst despot så som nødvendige.

På Svaneholms marker fandtes den gang flere landsbysamfund med gårde i forpagtning. De forpagtende bønder udførte hoveri på godset og betalte sin forpagtning in natura. Maclean forandrede hele dette system. Han slog agrene sammen, udstykkede jorden i betydeligt færre sammenhængende lodder (som regel kvadratiske), afskaffede hoveriet, indførte pengebaseret forpagtning og byggede en ny bondegård midt i hvert lod. Dette viste sig meget effektivt og godsets produktivitet øgedes betydeligt.

Maclean var, som en sand oplysningsmand, også aktiv i andet udviklingsarbejde. Han eksperimenterede med nye metoder og skrev lærebøger i landbrug. Han ville forbedre undervisningen i skolerne, byggede skoler og viste interesse for Pestalozzis pædagogik, som endnu i dag delvis kan ses som moderne. (Pestalozzi betonede evnen at indhente kundskab mere end selve kunskabsmængden.)

Rutger Maclean |

Svaneholm gods |

Udskiftningskort fra Svaneholm |

Udskiftninger i 1800-tallet |

Før og efter udskiftningen |

Andre fremsynede godsejere

De fremgangsrige forandringer på Svaneholm fulgtes op af andre godsejere. I 1802 traf Maclean overdirektøren for Landmålingen, Eric av Wetterström, til et møde i Helsingborg og overbeviste denne om fordelene med den udskiftning, som var blevet gennemført på Svaneholm. Idéerne kom den svenske konge Gustav IV Adolf for ører, og han bifaldt planen. I Skåne indførtes udskiftningen i 1803, og derefter spredtes reformen videre nordpå i landet. Det var imidlertid i Skåne, man gik mest hårdhændet frem, og allerede i 1825 var halvdelen af alle Skånes landsbyer blevet skiftet.

Produktionsforøgelse og statarsystemet

Nye og bedre kundskaber indenfor landbrug, samt udskiftningen resulterede i en højere produktivitet. Det gamle vekselbrug, med udelukkende korndyrkning varieret med braklægning, udskiftedes med flerårige dyrkningsmønster med både korn- og foderproduktion og med kun en lille del af jorden braklagt.

Samtidigt voksede interessen for anvendelse af nye maskiner og værktøj. Hoveriet afskaffedes, og i stedet opstod et proletariat af landarbejdere, da det specielle svenske statarsystem blev indført. Systemet indebar, at godsejeren fik faste, fuldtidsansatte landarbejdere til en lav omkostning. Lønnen udgjordes for en stor del af ”stat”, dvs. naturalier.

Kapitalisering af landbruget

Landbrugsrevolutionen medførte en kapitalisering af landbruget, og de sidste rester af det feudale system forsvandt. Godsejere og myndigheder tilskyndede revolutionen, mens almindelige bønder ville blive ved det gamle. Det var altså ikke en revolution, som førtes af de lavere samfundsklasser. Mange bønder følte, at de betalte en høj pris. Det gamle trygge landsbyfællesskab forsvandt, og gårde blev revet ned. En helt ny livsstil blev indført, som var præget af konkurrence og individualisme. Private interesser blev vigtigere end fællesskabet. Landskabet blev også kedeligere, da den gamle landsbygade forsvandt og naboen var flere kilometre væk.

Man kan godt forstå, at den nye pietistiske fromhed havde gode vækstmuligheder i disse omgivelser, og at den delvis kunne udkonkurrere den gamle kollektive religiøsitet. Mange bønder ramtes hårdt af forandringerne, som de oplevede som tvangsmæssige og uønskede.

På landet opstod nu kraftige modsætninger mellem samfundsklasserne. I de endnu uskiftede landsbyer sluttede man sig sammen for at undgå de nye idéer. Ved et bondeoprør (brødoprøret) i Malmö i 1799 viste hundreder af bønder deres utilfredshed med klasseforskellene. Fattige bønder angreb det etablerede samfund og truede det. Det gamle landsbyfællesskab kunne tydeligvis udgøre en fare for myndighederne.

Bondesoldater

Under Napoleonkrigen styrkedes bøndernes sammenhold yderligere imod magt og myndighed. Danmark og Sverige stod på den modsatte side i krigen mellem Frankrig og Storbritannien. Sverige truedes af krig fra Frankrig gennem dets allierede, Danmark. I 1808 blev det påbudt at opstille tropper. I Skåne blev det til seks bondebataljoner, hvor soldaterne levede under elendige forhold, uden ordentligt udstyr. Samme år udbrød der krig mellem Sverige og Finland. Det var hårde tider og mange døde af sult og sygdomme.

Esaias Tegnér besang disse bondesoldater:

”Hør den krigeriske røst! Den kommer fra øst,

den drøner som stormen ved fædrenes strand;

den kommer fra vest, den ubudne gæst.

Til strid, til strid for fædreland!”

(Fra krigssang til den skånske bondehær)

I 1811 skulle hæren på ny forstærkes pga. en skærpet udenrigspolitisk situation. Det blev pålagt de store godser at levere ekstra soldater, hvoraf det store flertal fortsat skulle komme fra bondestanden. 15.000 bønder og karle skulle forstærke hæren.

Bondeoprøret 1811

Nu var tålmodigheden sluppet op hos de skånske bønder. Udskiftningen havde tvunget dem væk fra trygheden; de var tvunget ud i en elendig bondehær, og nu skulle de tvinges ud i en ny krig. Der fremkom en bølge af protester, og der opstod en modstandsbevægelse.

I Kullaområdet var engagementet stort, og i begyndelsen af sommeren 1811 samledes 800 bønder og karle på Ringstorp i Helsingborg for at protestere, og det kom til uroligheder. Kampladsen var den samme, som hundrede år tidligere var skuepladsen for slaget ved Helsingborg. Det kom til uroligheder over hele Skåne og især i Klågerup og Torup ved Malmö blev bondeoptøjerne meget vanskelige at håndtere for myndighederne.

Til og med Rutger Maclean, den reformvenlige godsejer, blev angrebet af værnepligtsnægtende karle og bønder. Da han en sommeraften i 1811 kom hjem til Svaneholm, var gården pakket med mennesker. Han blev gennet op på sit værelse og tvunget til at underskrive en forsikring om, at han selv skulle sørge for soldater til hæren.

Hårde straffe

Myndighederne slog hårdt ned på oprøret, og man adviserede strenge straffe. En ejendommelig straf blev indført: Lodtrækning. Hvis den dømte trak et gevinstlod, fik han den udmålte straf, men hvis han trak en nitte blev straffen halshugning. Man skrev benådningsansøgninger til kongen, og da de endelige domme faldt den 4. januar, 1812, havde kong XIII ophævet al lodtrækning og ændret de fleste dødsdomme. Mange af oprørerne blev imidlertid idømt hudfletning (prygl), eller/og tab af hånden og fængsel.

Bondeoptøjerne i Skåne i 1811 blev voldsomme og var måske en medvirkende årsag til, at opdelingen af landsbyerne måtte gennemføres på en så hurtig og brutal måde. Måske var det ikke bare landbrugets effektivisering, man havde i tankerne, da man så hurtigt sprængte byfællesskabet i stykker. |