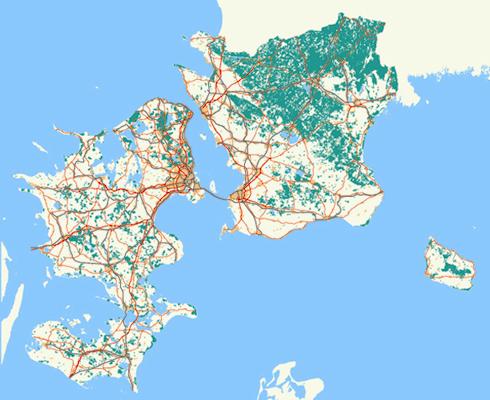

| Øresundsregionen

| | Øresundsregionen er en grænseoverskridende region i Nordeuropa imellem Danmark og Sverige. Regionen omfatter, Sjælland, Lolland-Falster, Bornholm og Skåne.

Øresundsregionens centrum er København. |

Europæisk regionalpolitik

| | Der findes rigtig mange fremstillinger af EU.s opbygning og udvikling, når det gælder Kommissionen, Ministerrådet, EU-parlamentet og udvidelserne siden starten med Romtraktaten tilbage i 1957. Mere upåagtet er udviklingen i EU.s regionalpolitik, selvom den får stigende betydning og voksende midler. |

Øresundsregionen og Europæisk regionalpolitik

Næsten overalt i Europas grænseregioner arbejdes der på forskellig vis med at overvinde de barrierer en national landegrænse historisk har skabt. Målsætningen er alle steder at skabe et mere integreret erhvervsliv og arbejdsmarked uden at eliminere forskelle i kultur og værdier. Bestræbelserne skaber alle steder interessekonflikter mellem regionerne og de nationale regeringer. I Øresundsregionen er det således regionalt valgte politikere i Østdanmark og i Skåne, der bestræber sig for at skabe samarbejde og nye udviklingsakser på tværs af den dansk-svenske grænse i Øresund.

Interreg regioner |

Starten på det europæiske samarbejde i 1948

Kampen for øget regional autonomi startede faktisk samtidig med, at de nationale regeringer i tiden umiddelbart efter 2. verdenskrig indså, at tættere europæisk samarbejde var det bedste alternativ til undgå ny krig i Europa. Kunne man spinde de europæiske landes økonomier sammen, ville ingen længere vælge krigen som løsning på konflikter. Dagsordenen blev sat med oprettelsen af Organisationen for Europæisk Økonomisk Samarbejde (OEEC) i 1948. Året efter etableredes Europarådet som en overordnet ramme for de konkrete samarbejdsbestræbelser i Europa.

I 1951 etableredes Kul- og Stålunionen, som i 1957 udviklede sig til Det Europæiske Fællesskab (EU). Nordisk Råd og EFTA oprettedes også i 1950´erne. Alle samarbejdsfora arbejdede som udgangspunkt for fremtidig fredelig sameksistens via økonomisk, politisk og kulturelt forpligtende samarbejde.

Samarbejdsbestræbelserne har været så en stor en succes, at nationalstaternes autoritet inden for egne grænser længe har været under pres fra regionale myndigheders ønske om større autonomi. Begrebet Regionernes Europa om fremtidens Europa skal ses i denne kontekst.

Europæisk regionalpolitik fødes i 1957

Både OEEC, Europarådet, Nordisk Råd og EFTA var såkaldte mellemstatslige samarbejdsorganer, hvor beslutninger skulle træffes i enstemmighed. Med Kul- og Stålunionen og senere EU forholdt det sig anderledes. Her fik føderale tanker i Frankrig, Vesttyskland, Italien, Holland, Belgien og Luxemborg sat sit stempel på et samarbejde med en vision om et fremtidens Europas Forenede Stater i Rom-traktaten, der fra 1957 udgjorde fundamentet for samarbejdet. De seks landekunne ikke få flere europæiske lande til at skrive under på Rom-traktaten som følge af de vidtgående unionstanker i Rom-traktaten.

De seks lande i EU fik dog i 1957 overtalt Europarådet til en at oprette en kommunalkongres (CLRAE), hvor folkevalgte politikere på regionalt og lokalt niveau kunne mødes i et debatforum og drøfte fælles problemer og løsningsmuligheder for europæiske regioners økonomiske udvikling. Det var de seks landes strategi med Kommunalkongressen at indsætte en trojansk hest hos landene uden for EU ved at mobilisere sub-nationale myndigheder. I Kommunalkongressen kunne regionerne så identificere, at deres naboregioner, som lå på den anden side af en nationalstatsgrænse, måske havde samme mål og ønsker for udviklingen, som ikke vandt gehør eller blev tilstrækkeligt bakket op med finansielle ressourcer fra regeringsniveauet. Med andre ord var Kommunalkongressen fødested for fælleseuropæisk regionalpolitik.

Øresundsrådet oprettes i 1963

Oprettelsen af Øresundsrådet i 1963 som en forløber for Öresundskomiteen skal ses i dette lys. Her sad ca. 30 regionalt valgte politikere fra Københavnsområdet og Skåne og drøftede bl. a. udformning og placering af en mulig fast Øresundsforbindelse samt andre spørgsmål af planmæssig karakter. Det må tilskrives Øresundsrådets fortjeneste i 1960-1970´erne, at en Øresundsforbindelse vedblev at blive drøftet som en forbindelse mellem København-Malmö ud fra betragtningen om en Ørestad på Amager og en ny storlufthavn på Saltholm. En ren dansk og svensk regeringstankegang ville formentlig have resulteret i en forbindelse Helsingør-Helsingborg, fordi afstanden København-Stockholm dermed tidsmæssigt kunne reduceres og være væsentlig billigere at anlægge som følge af den korte afstand i Øresund-nord.

Øresundsvision 1963 |

Luftfoto af den faste forbindelse |

Europarådets konvention og charter for regional selvbestemmelse

I 1966 fremsætte kommunalkongressen et forslag om at udforme en konvention med fælles europæiske regler og standarder for retten til regional selvbestemmelse på områder som infrastruktur, bolig- og erhvervslokalisering, velfærdsydelser m.v. Særligt problemerne i grænseregioner føres frem som et argument for at forpligte nationalstaterne til at overføre dele af sine beslutningsbeføjelser til de regionale niveauer. Europarådets parlamentariske forsamling, som består af politikere, der også sidder i de nationale parlamenter, vedtog ikke forslaget om en konvention, men indvilgede i at igangsætte en undersøgelse af den særlige problematik, der gør sig gældende i grænseregioner.

De europæiske grænseregioner organiserer sig

Europarådets undersøgelser førte dog ikke i første omgang til egentlige handlingsinitiativer. I 1971 dannede 10 europæiske grænseregioner derfor deres eget forum (AEBR). Ledende regioner i dette forum var de fransk-tyske grænseregioner omkring Rhinen samt den hollandsk-tyske Euregio-regionen mellem Enchede (NL) og Gronau (D). Det etablerede forum fik fra starten observatørstatus i Kommunalkongressen. Og senere kommer det grænseregionale forum til at spille en vigtig rolle ved udformningen af indholdet i EU.s Interreg-programmer for grænseregionalt samarbejde fra 1990.

EU: Medlemstallet udvides

1970´ernes oliekriser og økonomiske stagnation havde også sine konsekvenser for den gryende regionale bevidsthed om øget selvbestemmelse. Industrisamfundet var i krise og det ramte hårdt i København og i Skåne. Danmark var ellers sammen med Storbritannien og Irland blevet medlemmer af EU i 1973, hvilket burde have givet anledning til, at Folketingets politikere accepterede øget regionalt samkvem ud over den danske landegrænse. Dette var dog ikke tilfældet.

I øvrigt valgte Sverige at forblive uden for EU og føre en fortsat selvstændig økonomisk politik mere eller mindre uanfægtet af EU.

Den nordiske konvention om samarbejde i 1977

Nordisk Råd får i 1977 færdigbehandlet og vedtaget sin konvention om at tillade regionale samarbejdsaftaler i Norden samt indførelse af et fællesnordisk arbejdsmarked, en nordisk pasunion samt kultur- og uddannelsessamarbejde.

Konventionen fulgte dog i høj grad op på, hvad der allerede var eksisterende praksis mellem de nordiske lande. Egentlig regional autonomi og samkvem over Øresund var ikke på den politiske dagsorden i 1970´erne. At det forholdt sig på tilsvarende i hele Europa vidner Europarådets arbejde med en konvention for regionalt selvstyre.

Initiativet blev taget af Kommunalkongressen i 1966 og de europæiske grænseregioner fik organiseret sig i 1971. Men først i 1980 vedtog Europarådet en konvention på området, som opfordrer alle Europarådets medlemslande til at acceptere retten til regionalt selvstyre og grænseregionalt samarbejde.

Konventionen er dog uden bindende forpligtelser til at overføre suverænitet fra nationalt til regionalt niveau.

Konventionen blev i 1985 fulgt op af Europarådets vedtagelse af et egentligt charter for grundlæggende rettigheder for regional autonomi. Chartret blev vedtaget på initiativ fra det europæiske grænseregionale forum (AEBR) og befinder sig statusmæssigt på linie med chartret for menneskerettigheder. Chartret indeholder en finansiel pulje til bl. a. grænseoverskridende samarbejde mellem europæiske regioner og var som sådan den politiske beslutning, der senere dannede basis for EU.s Interreg-programmer fra 1990.

Gennembrud for europæisk regionalpolitik i 1983-1984

1983-84 markerede på flere måder vendepunktet for EU.s integrationsbestræbelser. De europæiske industrigiganter organiserer sig på europæisk plan på et initiativ af Volvokoncernens direktør Pehr Gyllenhammer i det der bliver til lobbyorganisationen "European Round Table of Industrialist" (ERT). Målet for ERT var en reel gennemførelse af det europæiske hjemmemarked for at forbedre vilkårerne for industriens konkurrence med Japan og USA. Midlet var bl.a. - udover lov- og regelharmoniseringer - omfattende investeringer i det europæiske vej- og jernbanenet, som faste forbindelse over Øresund og Femernbælt. Herved revitaliseredes også de grænseregionale samarbejdsformer rundt omkring i Europa og gav selvfølgelig også ny næring til det Øresundsregionale udviklingsperspektiv og argumentationen for en fast forbindelse.

I januar 1984 overtog Frankrigs daværende præsident Francois Mitterand formandsskabet i EU. Sammen med den vesttyske forbundskansler Helmut Kohl relanceredes Rom-traktatens bestræbelser om et europæisk hjemmemarked ved Det europæiske Råds møde i Fontainebleau i juni 1984. Relanceringen af et europæisk marked uden grænserelaterede barrierer fik hurtig betegnelsen "Det indre Marked". Og med dette begreb kom der som nævnt ny vitalitet i den europæiske politik for grænseregionerne.

Samtidig introducerede EU-Kommissionen sin nye vækstfilosofi, "The European Spatial Development Perspektiv" (ESDP), hvor regionerne selv skal generere deres økonomiske vækst ud fra egne styrkepositioner. Regioner måtte selv stå for en udviklingsplan og strukturfontsstøtten fra EU blev gjort additionel, dvs. at bevilgede EU-midler først udløses ved 50% medfinansiering fra de regionale parters side. Dette skal sikre, at strukturfontsmidler vitterligt bidrager til handlinger og projekter,som også nyder opbakning regionalt.

Europa-parlamentet bliver grænseregionernes platform i 1989

EU-parlamentet blev fra 1989 kampplads for grænseregionernes politiske projekt. Med Berlin murens fald i 1989 og udsigten til optagelse af adskillige østeuropæiske lande, hvoraf flere lande oplevede opblomstring af latente konflikter, som var holdt i ave under deres kommunistiske centralstyre, var en hovedopgave for EU og Europarådet nu at hjælpe til med at sikre demokratiets opbygning i Østeuropa.

Velfungerende grænseregioner i EU fungerede her som demonstrationsmodeller. De østeuropæiske folkegrupperinger kunne hermed overbevises om, at deres kulturelle identitet og eventuelle samhørighed med folkegrupper på den anden side af en national grænse ikke behøvedes at føre til oprettelse af en ny nationalstat med dertil hørende risiko for voldelige konflikter og borgerkrige.

Interreg-programmet oprettes i 1990

Sammenslutningen af grænseregioner (AEBR) havde derfor succes med at argumentere for, at Europa-Parlamentet sørgede for at lade 21 mill. ECU (nuEuro) fra strukturfontene fordeltes på såkaldte artikel 10-projekter til pilotprojekter i udvalgte grænseregioner. Disse artikel 10-projekter var forløberen for det første Interreg-program for perioden 1990-1993. EU-forfatningsmæssigt ses nationalstaternes anerkendelsen af regionernes stigende betydning for den europæiske integrationsproces med Maastricht-traktatens vedtagelse i 1992, hvor der oprettes et Regionsudvalg, som får høringsstatus på visse lovinitiativer fra EU-Kommissionen.

Øresundsregionen var ikke med i artikel 10-projekterne eller Interreg I 1990-1993. Diskussionerne i diverse europæiske fora om regionernes aktive rolle i Europas integrationsproces bidrager dog til forståelsen af det fokus danske og svenske regeringspolitikere havde på Øresundsregionen i 1990, og som førte til vedtagelsen af Øresundsbroen, Metro og Citytunnel samt igangsættelse af beslutningsprocessen for en Femernbæltforbindelse.

Øresundsregionen får sit eget EU-program

I 1993 oprettedes Öresundskomiteen til erstatning for Øresundsrådet. En af Öresundskomiteens første opgave var at få formuleret det konkrete indhold til et EU-program under strukturfontene (Interreg IIIA). Et sådant program fik regionen stillet i udsigt for perioden 1994-1999 inklusiv 13 mill. ECU (nu Euro). Indsatsområderne i Interreg IIA-programmet blev efterfølgende defineret som udvikling af regional ekspertise om Øresundsintegration, industri- og turismeudvikling, uddannelsessamarbejde, miljø og bæredygtig udvikling, infrastruktur, kultur og mediesamarbejde.

I alt igangsattes 59 Interreg IIA-programmer i de europæiske grænseregioner. Interreg IIA Øresundsregionen blev fulgt op med et Interreg IIIA-program for perioden 2000-2006. Interreg IIIA-programmet for Øresundsregionen har som overordnede indsatsområder: Nedbrydning af administrative barrierer, en social funktionel region og markedsføring af regionen som helhed.

Interreg-programmerne har bidraget til en eksplosiv vækst i antallet af Øresundsrelaterede samarbejdsorganer på mange områder af samfundslivet. Øresundssundsuniversitetet, Øresund Network, Medicon Valley Academy, Øresunds Science Region, IT Øresund, HH-samarbejdet, Info Business Øresund,Öresundsutveckling, Øresund Environment, undervisningsportalen Øresundstid, Pilelandet m.fl.

Opgavefordelingen mellem de mange Øresundsorganer er ikke veldefineret og nogle organisationer vil sandsynligvis ikke overleve, sådan som det allerede er sket for projektet Infotek Øresund, der var bibliotekernes forsøg på at samle deres kartoteker under en portal. Der mangler i øvrigt også stadig initiativer for etablering af Øresundsbaserede organer på vigtige områder som turismefremme og -markedsføring samt regional planlægning.

Øresundsregionen |

Den danske og svenske regering hjælper til...

Gode intentioner, lyst til samarbejde og et Interreg-program til at understøtte initiativerne giver ikke af sig selv integration over Øresund. Hvis Øresundsregionen skal blive en realitet, må befolkningerne på hver side af Øresund opleve regionen som en helhed, når det gælder studie-, arbejds- og kulturliv. Der findes barrierer for en sådan helhedsopfattelse, som beror på manglende information eller forskelle i de dansk-svensk kultur og mentalitet. Desuden skal personer, der pendler over Øresund for at arbejde eller studere, forholde sig til beskatning, lægebesøg, børnenes skole, erhvervelse af firmabil, hjemmearbejdsplads m.m. Her er det dog fortrinsvis en opgave for regeringsniveauet i Danmark og Sverige at sørge for, at det er praktisk muligt at bo på den ene side og have arbejde eller studier på den anden side Øresund.

Barrierer-rapporten i 1999

Den danske og svenske regering udarbejdede i 1999 en rapport: "Øresund - en region bliver til". I rapporten giver regeringerne udtryk for deres opfattelse af integrationsbestræbelser over Øresund: "Øresundsregionen har en unik mulighed for at udvikle sig til et grænseoverskridende regionalt kraftcentrum i Nordeuropa med international attraktionskraft med hensyn til virksomhedsetableringer og investeringer. Udviklingen i Øresundsregionen kan dermed, hvis den håndteres rigtigt af alle de aktører, der bidrager hertil, blive af stor værdi ikke kun i regionen selv, men for hele Sverige og Danmark.", samt at "Regeringerne i Danmark og Sverige deler helhjertet regionens entusiasme og fremtidstro og er parat til at yde et bidrag til, at visionen virkeliggøres.".

I rapporten opstiller regeringerne en række initiativer til yderligere at få fart på Øresundsintegrationen. Initiativerne vil blive igangsat på arbejdsmarkedet, det sociale område, skattepolitikken, infrastrukturen, erhvervspolitikken, byggesektoren, miljøspørgsmål, uddannelsesområdet og i kulturlivet.

Praktisk talt ingen af de beskrevne initiativer har medført praktiske politiske tiltag. Alene informationsindsatsen med initiativer som Øresunddirekt og centre for viden om dansk-svenske skatteforhold er blevet styrket. Der er derfor naturligt opstået utilfredshed blandt Øresundsregionens regionale myndigheder som følge af regeringernes reelle manglende vilje til at påtage sig et ansvar for en fortsat stadig tættere samkvem over Øresund. Den regionale utilfredshed er på ingen måde unik i dagens Europa. Kampen for øget regionalt autonomi står stadig mellem regeringsniveauet og de europæiske grænseregioner - ligesom i opstartsfasen tilbage i 1950´erne.

Forsiden til Barriere rapporten |

Øresundsbroen

| | Tanken om at forbinde Øresundsområdet til en sammenhængende region er ikke ny. De første konkrete broplaner kommer med industrialiseringen og det voksende samkvem i slutningen af 1800-tallet.

I 1900-tallets sidste årtier diskuteres ideen seriøst blandt beslutningstagere på begge sider af Øresund. |

Transportkorridor og koncept for Københavns byudvikling

Spørgsmålet om en fast forbindelse over Øresund blev allerede fra 2. verdenskrigs afslutning drøftet seriøst på regionalt og nationalt niveau i Danmark og Sverige. Den europæiske økonomi stod foran et nyt genopbygningsboom. I København og Skåne så man en fast forbindelse over Øresund som en mulighed for regionens økonomiske udvikling og styrkelse af funktionen som Skandinaviens naturlig gateway til kontinentet.

Øresundsbroen |

Fra hovedstad til europæisk metropol

Dansk Byplanlaboratorium, en forening af byplanlæggere, satte sig umiddelbart efter 2. verdenskrig sammen med hovedstadsregionens politikere og drøftede fremtidens byudvikling. Drøftelserne resulterede i 1947 i Fingerplanen. Fingerplanen var et forsøg på at samle udviklingsperspektivet inden for en planlægningsmæssig ramme, sådan at man undgik industrialiseringens hastige og tilfældige boligbebyggelse i de københavnske brokvarterer. Fremtidens byudvikling skulle finde sted i radiale infrastrukturlinier ud i mod købstadsringen Køge, Roskilde, Frederikssund, Hillerød og Helsingør. På disse radiale linier skulle stationscentre etableres som perler på en snor med tilhørende boligbebyggelse og detailhandel.

I København fandtes arbejdspladserne. Et udbygget S-togsnet i fingerplanstrukturen fik således tildelt den væsentlige opgave at transportere befolkningen mellem hjem og arbejde.

Efterhånden som bilejerskabet i 1960´erne blev muligt for de fleste udbyggedes også vejnettet i den radiale fingerplanstruktur. Områderne mellem fingrene blev defineret som grønne kiler reserveret til land- og skovbrug samt befolkningens rekreative adspredelser. I praksis frem til midten af 1970´erne kom den skitserede udvikling i Fingerplanen til at finde sted i Køgebugt- og Roskildefingrene, da politikerne så vidt muligt ønskede at friholde Nordsjællands landskabelige værdier fra byudviklingen.

Fingerplanen 1947 |

Øresundsstaden – en ny vision

Visionen om Øresundsbyen formuleres i 1959 af professor Peter Bredsdorf og hans svenske kollega Sune Lindström. Visionen blev tegnet på en serviet på en af Københavns kendte restauranter, Brønnums Café (Servietten opbevares på Dansk Byplanlaboratorium). På servietten ses faste forbindelser København-Malmö og Helsingør-Helsingborg. Sammenkoblingen af Kystbanen og Västkustbanan i nord og syd til en egentlig Øresundsring udgør regionens puls.

At radiale strukturer for boligbebyggelse og erhvervslokalisering således af Bredsdorf og Lindström var tænkt på tværs af Øresund lå faktisk i naturlig forlængelse af tankegangen bag fingerplanen fra 1947. Afstandsmæssigt er Malmö-Lund og Helsingborg faktisk ikke længere væk fra Københavns centrum end de øvrige byer i købstadsringen. Og de tre skånske byer kunne på hver deres måde styrke København som hovedstad. Malmö havde store virksomheder som skibsværftet Kockums. Og kun 20 km fra Malmö lå og ligger stadig uddannelsesbyen Lund med nordens største universitet. Helsingborg var og er også stadig det regionale centrum i Nordvestskåne med omfattende handels- og servicefunktioner for Sveriges relationer med det europæiske kontinent.

Også på nationalt niveau blev der tegnet faste forbindelser i perioden fra starten af 1950´erne. Den danske og svenske regering forpligtede sig ved et møde i Nordisk Råd i 1953 til at arbejde for en fast Øresundsforbindelse. Et dansk-svensk regeringsudvalg fremlagde i de næstfølgende 10-15 år adskillige forslag til linieføringer mellem København-Malmö og Helsingør-Helsingborg. Det var svenskerne som pressede på for en beslutning, men den daværende trafikminister i 1962, Kai Lindberg, fastslog, at beslutningen om Storebæltforbindelsen skal være truffet førend det danske Folketing skal bindes sammen med andre lande. Fra da af er dette officiel dansk politik.

Serviet fra Øresundsbyen |

Projektskitse for Øresundsforbindelse |

Projektskitse for Øresundsforbindelse |

Ørestaden drøftes i starten af 1960´erne.

Hvad der senere skulle vise sig at få afgørende betydning for placeringen af Øresundsbroen mellem København og Malmö var projekteringen af en ny bydel i Københavns Kommune, Ørestad, på Vestamager mellem Københavns City og Kastrup Lufthavn. I 1962 fik København en ny Overborgmester Urban Hansen, som blev valgt på et løfte om af bygge boliger. Urban Hansen så sig straks varm på lokaliteterne på Vestamager og Amager Fælled, som kommunen ejede sammen med Staten.

I 1964/65 afholdtes en arkitektkonkurrence for en ny bydel på området. I det vindende projekt blev der forudsat en Øresundsbro, tunnelbaner til Københavns City og en flytning af Kastrup Lufthavn til Saltholm. I selve forslaget indgik massiv boligbebyggelse i stationsnære amagerbyer på hver ca. 12.5000 mennesker, der var hægtet op på et effektivt S-togsystem efter tilsvarende principper som den byudvikling, der allerede var i gang i Køgebugt- og Roskildefingrene. 2. pladsen i arkitektkonkurrencen var et forslag, der byggede på den grundide, at København City skulle vokse sig udad fra den gamle middelalderby og i etaper ud over Vestamager. Den indkapslede by København skulle omdannes til den åbne Øresundsby efter visionen på P. Bredsdorf og S. Lindströms serviet.

Urbans plan

Urban Hansen var kendt og berygtet for sin foretagsomhed. I folkemunde blev han kaldt en ny 331V. Urban Hansens foretagsomhed på det vestlige amager rakte dog kun til kvarteret Remiseparken og Urbanplanen. Alt i alt var nybyggeriet på Amager faktisk ganske beskedent frem til slutningen af 1980´erne. Dårlige trafikale adgangsforhold til og fra øen fik politikerne til vægre sig mod en byudvikling på Amager. Det mest interessante ved arkitekt konkurrencen i1964/65 var, at én af de to forslagsstillere til 2. præmieprisen var Knud E. Rasmussen (Sorte-Knud), som i 1987 fik stillingen som plandirektør i Københavns Kommune, og som sådan spillede en rolle i udformningen af den Ørestad, som vi i dag ser konturerne af på Vestamager.

Tankerne om Ørestad er et bevis på, at Øresundsregionen og dens muligheder for at udvikle København som økonomisk kraftcenter var et aktuelt emne i 1960´erne. Det gik stærkt under højkonjukturen i 1960´erne. Antal biler på vejene eksploderede og hovedstadens arbejdsmarkedsopland bredte sig ikke alene til købstadsringen rundt om København, men helt ud til byer som Ringsted, Næstved og Slagelse, hvorfra folk hver dag pendlede til og fra arbejde i København.

Københavns første egentlige regionsplan, 1973

I 1967 påbegyndte hovedstadsregionens amter og kommuner drøftelserne for en revidering af fingerplanen for bedre at kunne indfange den hastige udvikling og det Øresundsregionale perspektiv. Drøftelserne fandt sted det såkaldte Egnsplanråd. De fremlagte planer blev i 1971 gjort til genstand for offentlig debat og resulterede i Regionplan 1973.

Regionplan 1973 brød med princippet om, at byudvikling skulle ske i en fingerplanstruktur med København som centrum. I stedet skulle der etableres en ny transportkorridor til vej og jernbane på tværs af fingrene i en korridor fra Køge over Høje Tåstrup og Allerød til Helsingør. Der hvor transportkorridoren krydsede fingrene skulle etableres centre for boliger og erhverv. Transportkorridoren skulle så føres videre over til Helsingborg enten nord om Helsingør ved Højstrup-Sofiero eller syd om byen via den såkaldte færgevejskorridor.

Regionplan 1973 indeholdte også planer om en Øresundsbro København-Malmö via Saltholm, hvor en ny lufthavn skulle etableres til erstatning for Kastrup Lufthavn.

Sverige beslutter sig for en Øresundsbro , 1973

Sideløbende med disse planer vedtog den svenske Riksdag i 1973 at anlægge en Øresundsforbindelse for tog og biler ved Helsingør-Helsingborg. Forslaget nåede aldrig at blive færdigbehandlet i det danske Folketing. Jordskredsvalget i 1973 blev udskrevet og herefter var Folketingets flertalskonstruktioner en kompleks affære, hvor spørgsmålet om statens udskrivning af skatter og deres anvendelse var blevet politisk springfarlige emner, hvorfor investeringer som Øresundsforbindelsen og Storebæltsbroen, der også stod foran en vedtagelse, blev udskudt. Samtidig startede også den første oliekrise med deraf følgende recession, arbejdsløshed og mærkbart mindre trafik på vej og jernbane.

Københavnsområdets Regionplan 1977

Hovedstadens Regionplan 1977 var et tydeligt bevis for det tilbageskridt 1970´erne var for de Øresundsregionale udviklingsperspektiver. Regionplanen omtaler ikke Øresundsforbindelser og en storlufthavn på Saltholm. Også på skånsk side var der vigende fokus på nødvendigheden af en fast Øresundsforbindelse. De skånske industrigiganter inden for skibsbygning og på områderne for fremstilling af tekstil og konfektion var i krise. I stedet satsede Skåne med succes på at blive Sverige "kornkammer" og vækstfokus flyttedes derfor fra eksportorientering til hjemmemarkedet. Med andre ord mistede byregionerne Malmö og Helsingborg betydning til fordel for Skånes landbrugsområder.

Danmarks medlemskab af EU fra 1973 kombineret med, at Sverige insisterede på at forholde sig uden for et forpligtende europæiske samarbejde, kan ligeledes forklare, at danskerne i 1970´erne vendte det nordiske og dermed også de Øresundsregionale udviklingsperspektiver ryggen. Det skulle dog senere vise sig, at netop det europæiske samarbejde og implementeringen af EU.s indre marked var drivkraften bag et revitaliseret fokus på Øresundsregionen og de skandinaviske relationer med det europæiske kontinent.

Industriens lobby

Omkring 1980 var arbejdet med at skabe et europæisk hjemmemarked uden nationale barrierer gået i stå. Dette gav anledning til stor bekymring i hele den europæiske industri, der gerne ville klare sig bedre i konkurrencen med USA og Japan. Volvodirektør Pehr Gyllenhammer tog derfor i 1983 initiativ til at etablere lobbyorganisationen "European Round Table of Industrialist" (ERT). Med i lobbyorganisation fandtes bl. a. direktørerne for stort set alle større europæiske industriforetagender som f.ex.. Philips, Siemens, Nestle, Unilever og Fiat.

I december 1984 udgav ERT rapporten "Missing links" med krav om etablering af bl.a. Øresundsbroen, Femernbælt og en opkobling af det skandinaviske jernbanenet til et vordende højhastighedsnet i Europa. Infrastrukturen skulle sammen med det indre marked være på plads. Industrien havde indset, at afhængigheden af stor lagringskapacitet for både færdigvare og komponenter optog ca. 40% af alle industriens investeringer. ERT ville derfor skabe grundlaget for indførelse af det japanske "Just-In-Time"-princip for produktion, dvs. at der først produceres, når kundens bestillingerne er foretaget, hvorfor kravet om præcision i leveringer gør hindringer som færgefart og grænseovergange til stopklodser.

Industriens lobby giver resultat

Volvo alene stod for 10% af Sveriges eksport i 1983. Og da den svenske regering i december 1984 besluttede at lukke skibsværftet i Uddevalla nord for Göteborg med 2.300 arbejdspladser trådte Pehr Gyllenhammar til. Han forhandlede sig frem til med den socialdemokratiske regering at lokalisere en Volvofabrik med 1.000 ansatte i Uddevalla, idet regeringen samtidig lovede at anlægge 40 km motorvej syd for Uddevalla. Dette var begyndelse til den skandinaviske link til Europa, der beskrives i ERT-rapporten "Missing links", og som reelt bandt den svenske regering op på at arbejde for en etablering af Øresundsbroen og Femernbæltforbindelsen.

Med den første succes i hus etablerede Pehr Gyllenhammar i 1984 den skandinaviske pendant til ERT, Skandinavian Link Konsortiet (Scan-link), med hovedsæde og sekretariat i Dansk Industris bygninger i København. Scanlink etableredes som aktieselskab med en ejerkreds af 55 erhvervsvirksomheder og banker i Norden. Formålet med Scan-link var først og fremmest at få den danske og svenske regering til at beslutte at anlægge Øresundsbroen og Femernbæltforbindelsen samt opbygge et sammenhængende motorvejs- og højklasse jernbanenet mellem Oslo, Göteborg. Stockholm, København og Hamborg.

Helsingør-Helsingborg og/eller København-Malmö

Det dansk-svenske regeringsudvalg fra 1950´erne fortsatte sin møderække og undersøgelser op igennem 1960-1970´erne for at drøfte mulige linieføringer over Øresund. Udvalgets arbejde nød ikke den store politiske bevågenhed førend deres forslag pludselig igen blev højaktuelle i 1984/85 med Scan-links etablering. Udvalgets betænkninger kredsede om en række linieføring mellem såvel Helsingør-Helsingborg som København-Malmö. Det forslag som man samfundsøkonomisk anså for bedst egnet var en både-og løsning, dvs. en jernbanetunnel Helsingør-Helsingborg og en 4-sporet motorvej København-Malmö.

I 1985 fik det dansk-svenske udvalg et nyt kommissorium. Udvalget skal vurdere en mulig etablering af en kombineret vej- og jernbaneforbindelse København-Malmö foruden en videre samfundsøkonomisk og miljømæssig vurdering af udvalgets tidligere studier. Hos DSB og SJ er holdningen i 1986 at arbejde for en ren jernbaneforbindelse København-Malmö. En holdning det danske Socialdemokrati delte med DSB. DSB igangsatte derfor egne undersøgelser af et sådant projekt sideløbende med det dansk-svenske udvalgsarbejde.

Storebæltbroen vedtages i 1986

12. juni 1986 besluttede det danske Folketing sig for etablering af Storebæltsbroen til vej- og jernbanetrafik. Dermed var vejen banet for en dansk stillingtagen og beslutning om en Øresundsforbindelse. Det politiske forlig om Storebæltsbroen indeholdte som kompensation til bekymrede jyske kommuner og borgmestre i Korsør og Nyborg, hhv. anlæg af motorveje i nord for Århus og udflytning af 2.500 statslige arbejdspladser på Flådestation Holmen til Korsør og Frederikshavn. Sidstnævnte beslutning fik betydning for, at en Øresundsforbindelse København-Malmö blev vedtaget i 1991.

Øresundsbroen: Nye undersøgelser 1987

I 1987 offentliggjorde det dansk-svenske udvalg sine undersøgelser om mulige Øresundsforbindelser og anbefalede nu en kombineret vej- og jernbaneforbindelse København-Malmö. Alternativet fra tidligere med en både-og løsning med vejforbindelse i København-Malmö og togtunnel Helsingør-Helsingborg fandtes dog stadig med som et alternativ. Særligt SJ var utilfredse med undersøgelsen, fordi en ren jernbanelinieføring København-Malmö ikke var undersøgt. Det dansk-svenske udvalg fik derfor et nyt kommissorium, hvor en ren jernbane løsning skulle undersøges i forhold til en kombineret vej- og jernbaneforbindelse. En linieføring Helsingør-Helsingborg var herefter taget af tapetet som en mulig Øresundsforbindelse.

Scan-link konsortiet blev ved sidstnævnte revision af kommissoriet bange for, at det dansk-svenske udvalg ville ende med at anbefale en ren jernbaneforbindelse, hvorfor konsortiet igangsatte egne samfundsøkonomiske beregninger af en sådan ren jernbaneforbindelse. Øresundsforbindelsen begyndte herefter spædt at møde folkelig modstand. En græsrodsbevægelse, "Scan-link Nej Tak", etableres i juni 1987, hvilket havde den effekt, at de miljømæssige konsekvenser af de mulige alternative linieføringer over Øresund prioriteredes i det følgende undersøgelser.

København får en udviklingsstrategi 1989

1988/89 var turbulente år i Øresundsbroens beslutningsproces, hvor politiske holdninger til projektet skiftede til fordel for en vedtagelse af en kombineret vej- og jernbaneforbindelse København-Malmö. Det hele startede, da Danmarks økonomiske problemer blev sat på den politiske dagsorden af et selvbestaltet "Forum for industriel udvikling" med den senere socialdemokratiske statsminister Poul Nyrup Rasmussen som en initiativtager. Analysen pegede på strukturproblemer i dansk industri og nødvendig satsning på forskning og mere vidensintensiv erhvervsudvikling.

Den daværende statsminister Poul Schlüter (K) ville ikke uden videre overlade initiativet til oppositionen, når talen faldt på fremtidens erhvervsudvikling. Derfor aftalte han sammen med den daværende formand for Socialdemokratiet Svend Auken at nedsætte en initiativgruppe i foråret 1989 med den opgave at fremkomme med ideer og forslag til en ny by- og erhvervsudviklingsstrategi for hovedstaden. I arbejdsgruppen var bl. a. placeret stærke socialdemokratiske borgmestre som Københavns Kommunes ny Overborgmester Jens Kramer-Mikkelsen, Amtsborgmester Per Kaalund i Københavns Amt, og LO.s daværende næstformand og nuværende formand Hans Jensen.

Initiativet skal ses i lyset af, at særligt København var særlig hårdt ramt af den økonomiske krise op igennem 1970-1980´erne. I den periode var det kendetegnende, at København oplevede virksomhedslukninger samtidig med, at den danske stat bevidst gennemførte udflytning af sine institutioner til provinsen og lagde sine infrastrukturinvesteringer i tillæg hertil. Lokaliseringen af TV2, Flådestation Holmen og dele af Erhvervsfremmestyrelse i provinsen er eksempler herpå.

Øresundsbroen: Nye undersøgelser 1989

Lige inden initiativgruppen gik i gang med sit arbejde offentliggjorde det dansk-svenske regeringsudvalg i februar 1989 sine nye undersøgelser. Ud fra samfundsøkonomiske betragtninger anbefaledes en kombineret vej- og jernbaneløsning, mens en ren jernbaneløsning anbefaledes ud fra miljømæssige hensyn. Finansieringen af den kombinerede Øresundsbindelse blev foreslået til at finde sted efter tilsvarende retningslinier som Storebæltsbroen, dvs. en brugerbetalt forbindelse, hvor prisen bestemmes ud fra niveauet på færgefarten Helsingør-Helsingborg. Togoperatørerne DSB og SJ skulle således ligesom ordningen på Storebælt årligt betale et givent fastsat beløb - uanset hvor mange togsæt der ville blive ført over dagligt.

Ved en ren jernbaneforbindelse skulle DSB og SJ derimod alene stå for finansiering og drift. Sidstnævnte forhold fik SJ til at ændre holdning og anbefale en kombineret vej- og jernbane. SJ var fra 1988 under privatisering og skulle nu til at tænke i markedsøkonomiske baner. Såfremt SJ blev tvunget til at finansiere store summer i en ren jernbaneforbindelse på Øresund, ville SJ reelt fravælge muligheden for at lade gods fragte via de sydsvenske Østersøruter til Tyskland og Polen.

Det markedsøkonmiske perspektiv sejrede med andre ord over det samfundsmæssige miljøhensyn. DSB fastholdte dog i første omgang sin fortsatte støtte til en ren jernbaneforbindelse, fordi man i DSB - også ud fra markedsøkonomiske principper - derved kunne man se frem til betaling for svensk jernbanegods transporteret gennem Danmark.

Initiativgruppens plan for København, 1989

Da initiativgruppen for hovedstadens udvikling senere i 1989 fremlagde sine ideer, blev planerne om en kombineret vej- og jernbaneforbindelse over Øresund, Ørestaden på Vestamager og en tunnelbane mellem Københavns city og Lufthavnen, fremholdt som de udviklingsperspektiver, der kunne få gang i hjulene. Som tunge argumenter for forslagene fremførte initiativgruppen, at Staten siden starten af 1970´erne reelt havde sat en stopper for trafikinvesteringer i hovedstaden, idet kun ca. 10% af statens investeringer havde tilfaldet Københavnsområdet, selvom ca. 85% af de mest trafikerede vejstrækninger i denne periode var i og omkring København. Argumentet om EU.s indre marked fra 1992 blev også anvendt, fordi København stod overfor at skulle ruste sig til Storby-konkurrence - ikke med Danmarks øvrige byer, men med metropoler som Stockholm, Hamborg og Berlin.

Würtzen-udvalget nedsættes i 1990

Initiativgruppens anbefalinger fik politisk opbakning i den siddende VKR-regering, selvom Det Radikale Venstre var modstandere af en kombineret vej- og jernbaneforbindelse. At anbefalingerne blev taget seriøst vidner Finansministeriets nedsættelse af det såkaldte Würtzen-udvalg i januar 1990, hvor arbejdet med en Øresundsbro og tunnelbane København, Ørestad og Kastrup Lufthavn således blev overflyttet fra Trafikministeriet. Würtzen-udvalget fik til opgave at udarbejde en sammenhængende plan for trafikinvesteringer i hovedstadsområdet og deres finansiering. Med inspiration fra de såkaldte britiske "New towns" var udvalgets forslag at finansiere en ny bybane fra Frederiksberg over Nørrebro til Ørestad og Kastrup Lufthavn ved grundsalg i Ørestaden til erhverv og boliger.

Manglende offentlige debat

Würtzen-udvalget offentliggjorde sit arbejde i begyndelsen af 1991 med en overrasket offentlighed som tilskuer. Arbejdet med planerne om Øresundsbroen og Ørestad var stort set foregået uden offentlighedens kendskab. Den folkelige opinion viste ellers i meningsmålinger en negativ holdning over for udbygningsplanerne på Amager inkl. Øresundsbroen. 12. december 1990 fik Danmark en ny VK-regering uden det skeptiske Radikale Venstre til en Øresundsbro med biler. I Sverige stod Socialdemokratiet til at tabe efterårets valg i 1991, og en borgerlig regering med et skeptisk Centerparti til Øresundsbroen fik regeringspolitikere i Danmark og Sverige til at handle hurtig. Den folkelige modstand nåede aldrig at blive tilstrækkeligt mobiliseret førend Øresundsbroen var vedtaget af begge regeringer over sommeren 1991. Og i foråret 1992 vedtog Folketinget ligeledes loven om anlæg af Ørestad efter anvisningerne i Würtzen-udvalgets oplæg.

De spektakulære planer for Hovedstadens byudvikling fik både Socialdemokratiet og DSB til i 1989-1990 at ændre holdning til fordel en kombineret vej- og jernbaneforbindelse. DSB.s motiver var stadig markedsøkonomiske, men ikke længere ud fra en godsbetragtning. En bycenterudvikling på Amager ville gøre Kastrup Lufthavn til en attraktiv togstation med trafik til og fra Københavns city, Malmö og Roskilde. Socialdemokratiets holdningsskifte må tillægges den politiske lobbyisme fra erhvervsgrupper som Scan-link og udsigten til at kunne fremskaffe arbejdspladser til de stærke socialdemokratiske borgmestre Jens Kramer-Mikkelsen og Per Kaalund.

Øresundsbroen: Efterspillet

Vedtagelsen af Øresundsbroen fik et besynderligt efterspil i efteråret 1993, hvor man på dansk side var i fuld gang med at bygge landanlæg, mens man på svensk side fortsat drøftede projektets miljømæssige aspekter. Selve projekteringen af Øresundsbroen skulle som sådan godkendes af Vattendomstolen bestående af en dommer, to ingeniører og to lægfolk. I Danmark troede man i lang tid, at Vattendomstolen ville standse bygningen af Øresundsbroen. Men Vattendomstolens kritik af broprojektet var en del af selve den svenske proces omkring den allerede vedtagne Øresundsbro. Så da Vattendomstolen sagde god for projektet, var broen færdigprojekteret.

I regeringsaftalen mellem Danmark og Sverige blev der indskrevet en klausul, dels om en prisparitet mellem brotaksten og færgebilletten Helsingør-Helsingborg, dels at den danske regering skal indlede forhandlinger med Tyskland om en Femernbæltforbindelse.

Prisproblematikken på Øresund er i dag til stadig til debat med udgangspunkt i broaftalens klasul om prisparitet. Femernbælt står foran sin endelige vedtagelse. Den danske og tyske regering er enige om hver især at stå for finansieringen af broens landanlæg, mens man fortsat ikke er nået til enighed om en finansieringsmodel for selve Femernbæltbroen til biler og jernbane.En region i vækst

| | I den avancerede industrialisering tidsalder har man fundet ud af at vækstpotentiale ikke kun beror på nationalstatens formåen, men primært handler om tilstedeværelsen af en række vækstfaktorer på tværs af landegrænserne. |

Beslutningen om Øresundsbroen blev ikke taget med det mål at skabe egentlig integration over Øresund. Det var snarere EU.s indre marked, udvidelse af EU mod Østeuropa og nødvendigheden af forbedret infrastruktur mellem Skandinavien og resten af Europa, der var på agendaen i 1991, da broaftalen mellem Danmark og Sverige blev indgået. Nok mente man broen ville få gavnlig effekt på en ellers økonomisk krise op igennem 1970-1980´erne i både København og Malmö. Men der var ingen der talte om at gå efter decideret Øresundsintegration, dvs. at erhvervsliv, arbejdsmarked og kulturliv skulle gøres lige så sammenknyttet over Øresund, som internt i Skåne og mellem København og kommunerne på Sjælland.

Nogenlunde samtidig med beslutningen om Øresundsbroen flyttedes fokus for, hvordan man i Europa så på de økonomiske vækstmuligheder. Urbane økonomier ansås for drivkraften. Udviklingen skulle drives ud fra storbyregioners egne styrker og forudsætninger i et samspil mellem universiteter og erhvervslivet. Skal man vurdere, hvorvidt København er en sådan storby og vækstregion, bliver Øresundsregionen interessant, fordi byområderne Malmö-Lund og Helsingborg kan blive integreret i Hovedstadsregionen.

Skal man vurdere, hvorvidt der så i dag finder en begyndene Øresundsintegration sted, så må man se på parametre som pendling, befolkningstilvækst, antal arbejdspladser, BNP m.m. i Øresundsregionen.

Debatten om Øresundsregionens muligheder...

På dansk og svensk side skal fortjenesten for, at Øresundsregionen kom på den politiske dagsorden, tilskrives debatskabende bøger i 1993-1994 fra Uffe Palludan, Christian Wichmann Matthiessen og Åke E. Andersson. Deres ærinde var at få politikernes opmærksomhed rette mod potentialet for en integreret Øresundsregionen. Ved at pege på Øresundsregionens samlede befolknings- og arbejdspladsvolume, koncentration af enkelte virksomhedsbrancher, antal godkendte patenter m.m. kunne det statistisk påvises, at regionens samlede volume gør den sammenlignelig med de store europæiske metropoler i aksen London-Frankfurt-Milano - også kaldet den blå banan. Paris ligger udenfor bananen, men anses dog for at tilhøre bananen.

Den blå banan |

Infrastruktur

Malmö-Lund området har ca. ½ mill. indbyggere. I et perspektiv med 70.000-90.000 køretøjer og 60.000 personrejser med tog pr. dag på vej- og jernbanenettet fra byerne i købstadsringen indtil København, er en daglig trafi kpå Øresundsbroen med ca. 10.000 køretøjer og 13.000 togpassagerer et sigende udtryk for, at Sjælland og Skåne endnu ikke er integreret på erhvervs- og arbejdsmarkedsområdet.

Det Københavnske udviklingsperspektiv er dog unikt i Europa med et byområde som Malmö-Lund i en tidsmæssig afstand på ca. 30-40 min. kørsel - og så ovenikøbet med en lufthavn inden for 15-30 min. rejsetid fra hvert byområde. Med den københavnske Metro ført igennem til lufthavnen i 2007 og citytunnelen i Malmö et par år senere, vil tilgængeligheden tidsmæssigt mindskes yderligere til et langt større antal specifikke rejsemål i selve Københavns- og Malmö-Lundområdet. Helsingborg med et opland på ca. 300.000 indbyggere er potentielt inden for samme tidsmæssige rækkevidde fra København med en fast forbindelse Helsingør-Helsingborg.

Ringbanen |

Pendlingen over Øresund

Den samlede pendling over Øresund er imidlertid stigende siden Øresundsbroens indvielse 1. juli 2000. Dog fra et relativt beskedent niveau på ca. 2000 personer i 1997 til ca. 3.750 personer i 2001, som pendler fra Skåne til Sjælland. Den modsatte vej, fra Sjælland til Skåne, har niveauet siden 1997 været konstant på ca. 200 pendlere. To undersøgelser foretaget af henholdsvis Københavns og Helsingør Kommuner estimerer ca. 5-7 gange flere rejsende på Øresundsbroen og via Helsingør-Helsingborg ved fuld integration, dvs. befolkningen på Sjælland og i Skåne udviser samme mobilitet over Øresund som den trafik vi oplever imellem kommunerne i hhv. hovedstadsområdet og i Skåne.

Pendlere fra Skåne til Sjælland |

Det internationale perspektiv

Forudsætningerne for Øresundsregionens internationale kontakter med hele Østersøregionen og resten af verden er også optimale. Københavns Lufthavn er det Skandinaviske hub for transittrafik til og fra Østersøen, Europa og de oversøiske ruter. 60 % af flypassagerer i Kastrup Lufthavn er såkaldte transitpassagerer. Dette betyder, at SAS rentabelt kan have mange direkte flyruter ud af Skandinavien. Kastrups Lufthavn stærke position er et godt udgangspunkt for at tiltrække internationale virksomheder til lokalisering i Øresundsregionen.

Infrastruktur: Hvem delte ansvar

Ansvaret for varetage udviklingen af en infrastruktur i et Øresundsregionalt perspektiv er ikke samlet hos én myndighed, men delt mellem adskillige myndigheder på nationalt og regionalt niveau. Et kompliceret spil af interesser kan derfor iagttages, når der skal tages beslutninger om trafikanlæg og -betjening over Øresund. Hovedstadens Udviklingsråd (HUR) og Region Skåne er på regionalt plan ansvarlige for den overordnede koordinering på trafikområdet. Men det er staterne, der har beslutningsmyndigheden omkring faste forbindelser og takstpolitikken på Øresundsbroen. DSB og Region Skåne har ansvaret for togkørsel over Øresundsbroen, og på dansk side er bus-, Metro- og S-togsdrift opdelt i selvstændige selskabskonstruktioner.

Øresundsregionen og erhvervsudvikling

Ligesom på infrastrukturområdet er der ingen enkelt myndighed, der har ansvaret for en skabelse af en Øresundsbaseret erhvervsudvikling. Her må alle erhvervsfremmeaktører som f.ex. kommunale erhvervskontorer, forskerparker og rådgivningen på iværksætterområdet koordinere deres indsats og være enige om mål og midler for at skabe de bedste rammer for Øresundsregional erhvervsudvikling. Også ansvaret for den regionale lokalisering af erhvervsarealer, boliger og rekreative områder er fordelt på flere myndigheder. HUR har ansvaret i Hovedstadsregionen, mens kommunerne i Skåne selv har bemyndigelse omkring arealanvendelsen.

Det synes givet, at erhvervsudvikling i et Øresundsperspektiv må finde sted for vidensbaserede produkter og serviceydelser. Og netop på disse områder er den internationale konkurrence mellem storbyregioner allerede i fuld gang. Et meget vigtigt element for Øresundsregionen er tilstedeværelsen af højt specialiseret uddannet arbejdskraft fra universitetsmiljøerne på begge sider af Sundet. Dette kan vise sig have såkaldte synergieffekter både som følge af den samlede volume i regionen som helhed, og det at to hidtil adskilte vidensmiljøer bringes sammen.

BNP og BRP |

Platforme for erhvervsudviklingen

For at opnå en vidensbaseret erhvervsudvikling har de regionale myndigheder via samarbejdet i Öresundskomiteen opbygget såkaldte platforme omkring koordinering og fælles branding af erhvervsfremmeaktiviteterne på udvalgte områder. Medicon Valley Academy på biotekområdet er nok den mest kendte Øresundsregionale platform. Men også IT Øresund og Øresund Food Network er eksempler på platforme for hhv. informationsteknologi og levnedsmiddelindustrien.

Erhvervsudviklingsområderne

Såkaldte specialiseringsprofiler for hhv. Hovedstadsregionen og byområderne Malmö/Lund og Helsingborg er indikatorer for, hvilke områder, der kan tænkes at blive fremtidens lokomotiver for erhvervsudviklingen. I tabel 1 angives specialiseringsprofiler for antal branchebeskæftigede for hhv. Hovedstadsregionen, Malmö-Lund og Helsingborg. Tabel 1 er opgjort som branchens andel af beskæftigede i regionen i forhold til andelen i hhv. Danmark og Sverige. Danske og svenske statistiske brancheoplysninger er ikke identiske, menkonklusioner kan alligevel drages.

Tabel 1: Specialiseringsprofil i Öresundsregionen 2000 (koncentrationsindex) Hovedstadsregionen | Malmö-Lund | Helsingborg-Landskrona | Läkemedelsindustri | 2,38 | Förpackningsindustri | 4,80 | Tillv. medicinsk-teknisk utrustning | 3,21 | Försäkring och finans | 2,23 | Medicinsk F & U | 4,37 | Grafisk industri | 2,63 | Forskning & Utveckling | 1,91 | Tillv. medicinsk-teknisk utrustning | 2,12 | Livsmedelsindustri | 2,43 |

Kilde: Danmarks Statistik - Registerbaseret arbejdsstyrkestatistik, 1.januar 2001 (november 2000), Beskæftigede personer med arbejdssted i Danmarkfordelt efter erhvervsgruppe (DS111) og arbejdsstedets beliggenhed, SCB – RAPS,Förvärvsarbetande 16+ år (dagbefolkning) efter bransch (5-siffrig SNI92) efterregion, bransch och tid.

Tabel 1 viser, at medico-området, dvs. både F&U-aktiviteter, fremstilling af medicin og medicinsk udstyr, i både Danmark og Sverige er koncentreret i Hovedstadsregionen og i Skåne.

På dansk side er lokomotiverne Novo Nordisk og Lundbeck hhv. med salg af diabetesmedicin og medicin til psykisk syge.

På skånsk side kan nævnes AstraZeneca med salg af mavesår og kolesterolsænkende medicin. Øresundsregionens medico-industri har i alt 26.000 ansatte. Det svarer til omkring halvdelen af totalt antal ansatte i Danmark og Sverige.

I København findes desuden en koncentration af forsikrings- og finansbranchen med f.eks. hovedkontorer for Codan, Danica og Nordea.

Forlagsbranchen er stærkt repræsenteret med f.ex. Egmont, Allers, som også har store filialer i Helsingborg.

Emballageindustrien forefindes i Malmö med f.eks. Tetra Pak og Rexam.

Koncentrationen af levnedsmiddelbranchen i Helsingborg skal tilskrives byens tradition som Sveriges port til kontinentet, hvorfor en række fødevarevirksomheder her har valgt at lokalisere sine fordelings- og lastningscentraler.

Lokaliseringen af en filial af Lunds Universitet i Helsingborg (Campus Helsingborg) har bl. a. ført til tanker om at udvikle Helsingør-Helsingborg til et maritimt forskningsmiljø i international klasse ved at samle Københavns Universitets forskningsaktiviteter på området i Hillerød og Helsingør med Lunds Universitets aktiviteter på samme områder. Foreløbig er disse planer dog ikke gennemført.

Hvor langt er vi med integrationen over Øresund

Selvom arbejdspendling over Øresund fra Skåne til Sjælland er i vækst, så sker dette fra et ganske beskedent niveau i forhold til den pendling, der kan iagttages mellem kommunerne hhv. i Hovedstadsregionen og i Skåne. Parametre for regionens attraktivitet er de forhold, at Hovedstadsregionen og Skåne fra midten af 1990´erne har oplevet en befolkningstilvækst på ca. 3-4 % og vækst i antal arbejdspladser, som årligt har svinget mellem ½-3½ %. Sådanne vækstrater skal måske ikke skal tilskrives Øresundsintegrationen som sådan, men i hvert fald det faktum, at området omkring Øresund er blevet mere attraktivt lokaliseringssteder for arbejdspladser og bosætning. Denne konklusion styrkes ved at kaste et blik på det regionale BNP - også kaldet BRP - for Hovedstadsregionen, Skåne samt Øresundsregionen. BRP udviser nemlig fra 2001 en højere vækstrate end gennemsnittet for BNP for Danmark og Sverige som helhed.

I forhold til den udviklingsoptimisme, der herskede omkring

Øresundsintegrationen op til Øresundsbroens åbning 1. juli 2000, synes der i dag at være enighed om, at integrationsprocessen komme til at tage længere tid end først antaget. Den økonomiske recession efter IT-branchens økonomiske nedtur fra 2000 er givetvis en del af forklaringen. Skal der peges på mere Øresundsspecifikke forklaringer, så synes debatten at koncentrerer sig om følgende områder: 1. Prisen for at passere Øresund 2. Forskellige love og regler for beskatning på arbejdsmarkedsområdet 3. Forskelle i kultur og mentalitet.

Hvilken af de tre områder, der skal tilskrives at være den væsentligste faktor for den langsommelige Øresundsintegration er umuligt at afgøre og afhænger under alle omstændigheder af, hvilke områder, der drøftes.

Alt i alt må det dog konkluderes, at Øresundsintegrationen og det at leve og bo ved Øresund igennem de sidste 10 år er blevet et tema, som kommer frem i debatten, når udviklingen skal drøftes i Hovedstadsregionen og i Skåne.

H-H aksen |

|