| Første verdenskrig

| | Under Første Verdenskrig lykkedes det de nordiske lande at holde sig neutrale, men de krigsførende lande stillede bl.a. krav om minering af Øresund.

Det lykkedes også at samordne udenrigspolitikken under krigen, men bagefter var der stor uenighed om fortsættelse af neutralitetspolitikken og det udenrigspolitisk samarbejde. |

1. verdenskrig

Under Første Verdenskrig lykkedes det de nordiske lande at holde sig neutrale, men de krigsførende lande stillede bl.a. krav om minering af Øresund. Det lykkedes også at samordne udenrigspolitikken under krigen, men bagefter var der stor uenighed om fortsættelse af neutralitetspolitikken og det udenrigspolitisk samarbejde.

Et neutralt Norden

Ved krigens udbrud erklærede Danmark, Norge og Sverige sig neutrale i forhold til de to stormagtsblokke. Dette var delvis et resultat af et diplomatisk samarbejde, som fandt sted før krigsudbruddet. Allerede i 1909 og 1910 forhandledes om fælles neutralitetsinitiativer, og en aftale var på plads i 1912. Skandinavernes neutralitetserklæring var således velforberedt og de tre lande protesterede i fællesskab mod såvel den engelske opfattelse, at hele Nordsøen var at betragte som krigsområde, som tyskernes mineblokade af Øresund og bælterne.

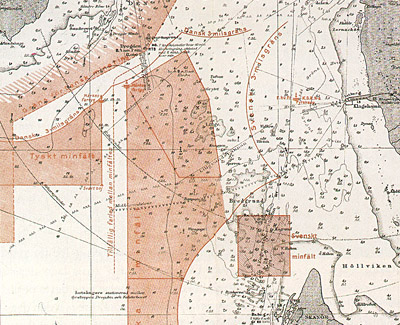

Minefelter i Øresund |

Malmømødet

For yderligere at befæste den fællesnordiske linie samledes de tre skandinaviske konger på det såkaldte Trekongemøde, med deres udenrigsministre i Malmø den 18. – 19. december 1914. Malmøs muligheder for at arrangere den slags topmøde var den gang meget begrænsede, men med lidt god vilje kunne deltagerne indlogeres på forskellig vis. Kong Christian boede hos Herslow, Haakon hos enken Kockum og Gustav hos landshøvdingen, mens udenrigsministrene Scavenius, Ihlen og Wallenberg boede på Hotel Kramer.

Bag en pragtfuld ramme af studentersangere fra Lund, vinkende fra balkoner, museums- og kirkebesøg, pågik det diplomatiske arbejde. Resultatet fra mødet blev en ny god vilje til øget skandinavisk samarbejde. Det var indlysende at sårene efter Danmarks tab ved den tyske grænse og efter Norges frigørelse fra Sverige nu var helet. Hjalmar Branting skrev i sin avis, at man nu kunne se et glimt af ”Nordens Forenede Stater, i gang med at dannes under frie former”.

Tre nordiske konger 1914 |

Tre nordiske konger |

Tre nordiske konger |

Skandinavismen genoplives

Mødet havde åbenbart igen vækket visse skandinavistiske forhåbninger og det blev efterfulgt af flere interskandinavistiske sammenkomster. I København samledes stats- og udenrigsministrene i marts 1916 og i Kristiania (Oslo) blev et ministermøde holdt i september samme år. Alle tre lande havde problemer med krænkelser, begået af de krigsførende lande mod de neutrale. Særlig problematisk blev spørgsmålet om adgangen til Østersøen. Her havnede både Danmark og Sverige i diplomatisk knibe.

Mineringen af Øresund

Tyskland havde fri passage mellem Nordsøen og Østersøen via Kielerkanalen, men var selvfølgelig interesseret i, at England ikke fik den samme mulighed for adgang til Østersøen. Tyskerne krævede derfor, at bælterne skulle spærres med miner.

Neutralitetserklæringen fra de skandinaviske lande betød, at ingen af siderne skulle gives fordele. Danskerne, som var økonomisk afhængige af England, havnede i en svær situation. Hvis danskerne sagde nej til det tyske krav, ville tyskerne alligevel minere bælterne og så stod det kun en ting tilbage for danskerne, at angribe Tyskland, et på forhånd håbløst foretagende. Danmark ville også gerne sikre sin indenrigs- søfart og i sidste ende bestemte man, at afspærre bælterne.

Meningerne om beslutningen var delte i den danske regering, men Christian X.s ord vejede tungt. Han mente, at Danmark var nødt til at føje sig efter de tyske krav. Øresund blev således englændernes eneste adgangsmulighed til Østersøen.

Tysk Pres

Den svenske regering afviste det tyske krav om minering af den svenske side af Øresund, men accepterede at slukke for alle fyr og lysebøjer i sundet for at vanskeliggøre passage. Tyskerne afspærrede internationalt farvand syd for sundet for yderligere at begrænse adgangen, men der fandtes endnu en sejlrende, tæt på Skanör, hvor fartøjer kunne passere. Denne, Kogrundsrännan, krævede tyskerne nu mineret og svenskerne føjede sig endeligt i sommeren 1916. Østersøen var således helt lukket for engelske fartøjer og næsten 100 engelske skibe forblev indelukket i Østersøen. Kun én minefri passage blev tilbage, og den blev bevogtet af svenske krigsskibe, som skulle sikre at kun svenske skibe passerede.

Tyskvenlig neutralitet

Den tyske flåde blev således meget dominerende i området. Det havde stor betydning for den svenske beslutning, at Gustav V.s dronning, Viktoria, kraftigt havde påvirket kongen i tyskvenlig retning. Dette gjaldt også statsminister Hammarskjölds opfattelse af neutralitetens karakter. Han havde lovet Berlin, at Sverige ville opretholde en ”velvillig neutralitet”, mens de allierede havde fået besked om en ”streng svensk neutralitet”.

Tyskerne prøvede flere gange, at få Sverige engageret i krigen. Prins Max af Baden, som var beslægtet med den svenske dronning Viktoria, tog aktiv del i disse pressionsforsøg. Kongeparret var interesseret, men regeringen var indbyrdes uenig. Udenrigsminister Wallenberg ville gerne vise mere sympati overfor England og den socialistiske opposition, med Branting som leder, krævede streng neutralitet, også mod Tyskland.

Sverige på tysk side

Den svenske regerings forhold til Storbritannien var spændt, ja mere spændt end forholdet mellem Danmark og Storbritannien. Danmarks regering havde sluttet en aftale med Storbritannien om import af varer, mod at Danmark garanterede at de ikke blev videresolgt til Tyskland. Den svenske statsminister afviste en lignende aftale og derfor blev Sverige ramt af en følelig mangel på varer. Manglen var særligt alvorlig i vinteren 1916-17, da Hammarskjöld fik øgenavnet ”Hungerskjöld”.

Forholdet mellem de allierede og Sverige blev endnu mere anstrengt, da det stod klart, at den svenske regering havde hjulpet tyskerne med befordring af chiffertelegrammer, fra den tyske regering til tyske interessevaretagere, via det svenske udenrigsdepartement. Allerede før denne skandale blev afsløret, havde en regeringskrise tvunget den svenske regering til at træde tilbage, til fordel for en konservativ regering, som sad ved magten fra marts til september 1917. Da vandt venstrekræfterne ved valget til rigsdagens andenkammer, og en ny regering under ledelse af Nils Edén tiltrådte, med Hjalmar Branting som finansminister. Det blev en koalitionsregering mellem socialdemokrater og de liberale.

Skandinavien under økonomisk pres

Den tyske totale ubådskrig ramte både den danske og svenske handelsflåde. Da USA i 1917 gik med i krigen, fik England forsyninger med amerikansk hjælp. Konvojer ledsagede transporterne over Atlanten, og England var dermed ikke mere afhængig af varer fra Danmark og Sverige. Dette truede i høj grad den danske og svenske økonomi. Den engelske vrede over den danske og svenske eftergivenhed overfor tyskerne blev kostbar for skandinaverne. Desuden medførte den totale ubådskrig, at varetransporterne til Danmark og Sverige vanskeliggjordes.

Alt dette førte til, at Kogrundsrännan blev genåbnet i 1918. Den mindskede handel med stormagterne i Europa førte dog til at handelen mellem de nordiske lande øgede. Den nye svenske regering arbejdede hårdt for at opnå bedre relationer med de allierede. Anstrengelserne var ikke helt uden resultat, først og fremmest takket være den svenske forhandlingsleder Marcus Wallenbergs gode forbindelser til den britiske blokademinister.

Normalisering

Ved krigsafslutningen i november 1918 begyndte handelen atter at komme i gang. Råvaremangelen var imidlertid stor og priserne steg. Dette førte til øgede krav om lønstigninger, og der forekom en række strejker og voldsomme demonstrationer, ikke mindst i København. Men Danmark og Sverige var, trods alt, sluppet billigt fra den første verdenskrig. De nordiske lande udvikledes til stabile demokratier og kvindelig stemmeret blev indført i hele Norden. Kontakterne mellem de europæiske stater blev genoptaget, den voksende luftfart gjorde afstanden mindre og nedrustningsforhandlinger og Nationernes Forbund gav forhåbninger om en lys fremtid.

Hvis forholdet mellem de tre nordiske stater umiddelbart efter opløsningen af unionen mellem Sverige og Norge i 1905 havde været noget anstrengt, gav erfaringsgrundlaget fra neutralitetspolitikken en vis fælles platform, selvom kredse i Danmark havde set med ængstelse på den svensk-tyske tilnærmelse.

Ned- og oprustning

I Danmark blev nedrustningspolitikken i årene fremover en grundsten i regeringssamarbejdet imellem Socialdemokratiet og partiet Det radikale Venstre, som dannede regering første gang 1924-26 og igen fra 1929 og helt frem til Danmarks besættelse i 1940. Forholdet til Tyskland blev det afgørende spørgsmål: Kunne og skulle man gøre modstand, hvis en stormagt overfaldt Danmark? De radikale fastholdt at det var nytteløst, men i Socialdemokratiet var der voksende modstand imod nedrustningen. Et forsvarsforlig imellem de to partier i 1937 betød reelt en forhøjelse af forsvarsbudgettet.

Nordens Lænkehund

Samme år startede en debat om et fælles nordisk forsvarsforbund til opretholdelse af neutraliteten. I Sverige betragtede vide kredse en trussel imod Danmark og Finland som ensbetydende med en trussel imod Sverige og man påbegyndte en kraftig oprustning, som også fandt vej som argument i den danske debat. Faktum var dog, at de øvrige landes regeringer fandt det alt for risikofyldt at indgå et forsvarsforbund med Danmark, som lå så tæt på det nu åbenlyst aggressive Tyskland. Den danske statsminister Stauning var tydeligt irriteret over debatten og reagerede i en tale i Lund i marts 1937 med skarpe vendinger at afvise rollen som Nordens Lænkehund:

"Jeg har set den begrundelse anført, at Norge, Sverige og Finland vil føle sig utrygge, hvis Danmark ikke indretter et værn ved den danske sydgrænse, som Sverige kan godkende, Er det ikke en farlig betragtning? Jeg tænker heller ikke, at nogen ansvarlig mand går ind for den. Har Danmark fået overdraget opgaven som lænkehund eller anden vagtopgave på Nordens vegne? Mig bekendt har der aldrig været forhandlet om noget sådant. Af historien ved vi, at det var en udbredt formodning i 1864, at svenske tropper ville komme Danmark til hjælp i den da påtvungne krig. Der kom selvfølgelig ingen”.

Thorvald Stauning |

|